(L-R) Chantell Cleversey (IMP Class of 2021) and Meghan Robinson

(This article was originally posted on March 15, 2019. It was updated on August 28, 2019.)

Chantell Cleversey (IMP Class of 2021) is trying something few others have: using human fat to 3D bioprint breast tissue. More particularly, she is trying to bioprint tissue that could be used for breast reconstruction following mastectomy.

“It could be incredibly honouring to do that for someone,” says Chantell, who has a keen interest in plastic surgery.

To create the tissue, the research team—lead by Chantell and lab manager Meghan Robinson—is using liposuction fat and alginate, an inert gel that will hopefully make the new tissue easier to implant by providing additional stiffness. In practical application, the fat would come directly from the mastectomy patient, creating a replacement tissue most similar to that lost and lessening the chance of rejection.

Rejection, however, isn’t the first hurdle the team faces; it’s the fact that breast tissue is difficult to keep alive in the quantity needed for breast reconstruction. Chantell and Meghan say the most anyone has managed to create and keep viable is 10 mL.

“It’s a really needy tissue. It needs a lot of nutrients,” Meghan explains.

And the key to getting nutrients to that tissue: blood vessels. While fat contains plenty of stem cells and other valuable components to naturally promote the development of blood vessels, it’s not enough to sustain a large amount of unaltered implanted tissue. That’s why the team has turned to 3D bioprinting. A 3D bioprinter lays down cells suspended in alginate one layer at a time, allowing for the placement of blood vessel–forming cells deep inside the tissue. As stated in the research outline, the bioprinter can also print “empty architecture” to allow for greater diffusion of nutrients and oxygen within the tissue. This helps to circumvent the issue of tissue death, which has been seen in previous studies that tried implanting unaltered tissue.

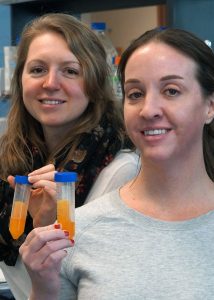

Chantell and Meghan showcase some of the fat they’re using to conduct their research.

Currently, the team is trying to figure out if they can use the liposuction fat as-is, or if they need to separate the stem cells out for bioprinting.

While it’s too early to know if this method will succeed, both Chantell and Meghan say “so far, so good.” If all goes well, they hope to create a small piece (1–3 cm3) of healthy, long-term breast tissue with good structural integrity—or as Meaghan says, tissue that will “not die and fall apart.”

For Chantell, results that show proper cell and blood vessel growth would not only prove the materials provide the right resources for healthy tissue, but that the research could be continued and holds promise for further study.

“I’d like to see it go on, and progress to model studies and subsequently contribute to a solution for breast reconstruction” she says.

Whether she’ll be a part of that future work is yet to be determined, however. Chantell is conducting the current research for her second-year FLEX project, which comes to an end in May.

She says any other IMP students interested in taking over the FLEX project, or taking it in another direction, can contact her or her supervisor, Dr. Stephanie Willerth.

UPDATE

Chantell, Meghan and their team have successfully managed to 3D print breast tissue using human fat. However, they haven’t completed full analyses due to equipment delays, and thus have few results to share.

“The limited analyses we’ve completed concluded that there was a promising cell-survival rate immediately post-print – that is, the cells tolerated printing process well,” says Chantell. “This is important because we need live cells to promote tissue generation within the printed construct.”

The team is currently planning another print, as equipment issues have been resolved, and they plan to have further results this fall. They also eventually aim to publish their findings.

In the meantime, Chantell, Meghan and Dr. Willerth have published “3D Printing Breast Tissue Models: A Review of Past Work and Directions for Future Work” in Micromachines.

“Given my interest in reconstructive surgery, and the current and future role 3D printing will have, I thought it was an important opportunity to share the summarized research that myself and my co-authors have reviewed in preparation of 3D printing a construct of our own,” says Chantell. “This provides the scientific and clinical community a quick and easy glimpse of what has been done thus far and what strides could be taken next.”